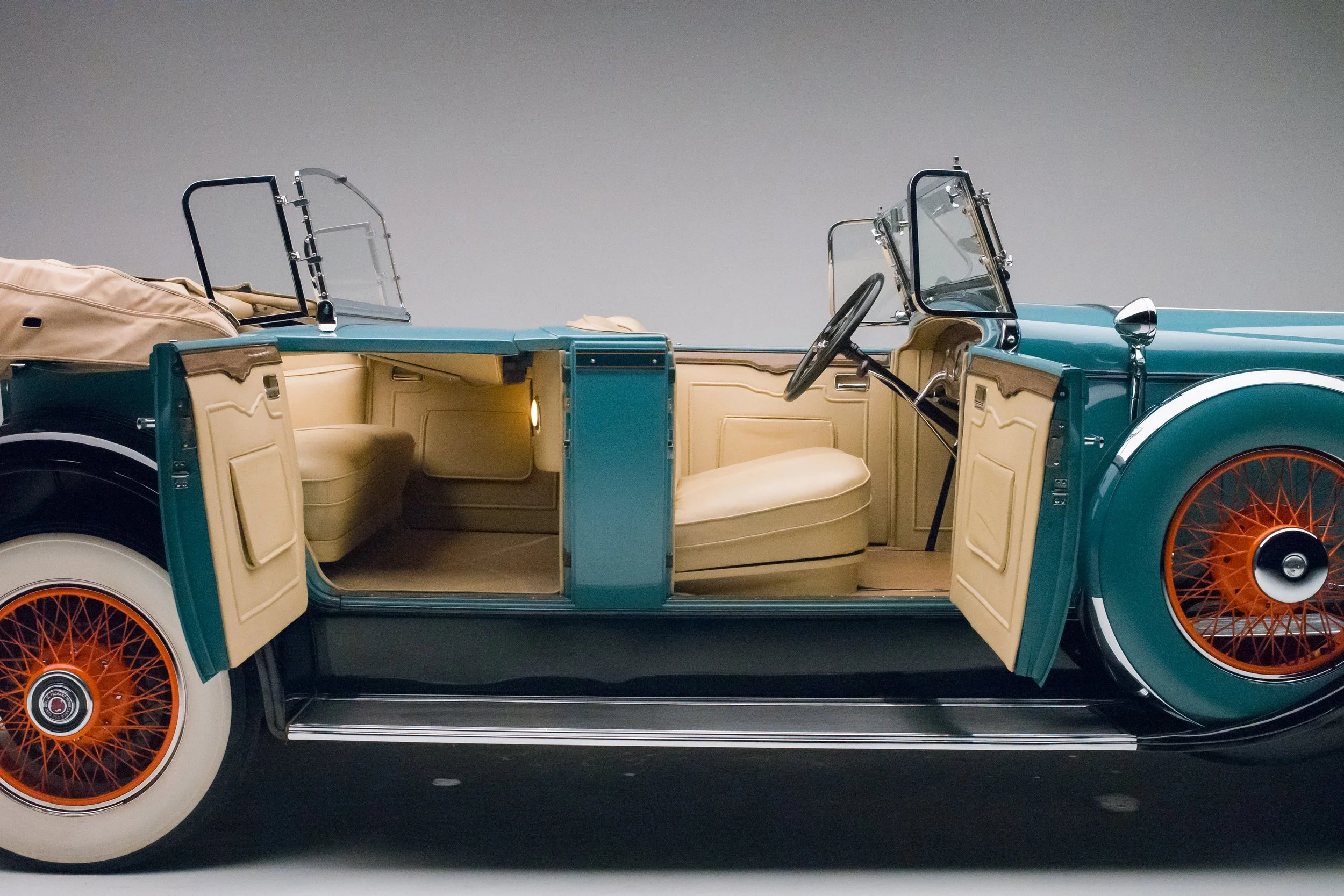

1929 Packard 645 Dual Cowl Phaeton

1929 Packard 645 Dual Cowl Phaeton

By any measure, 1929 was the best in Packard’s history. Their name was golden but unlike some of the other fine car makers, they had the volume to back up their reputation, selling just under 50,000 cars in 1928 and about 55,000 in 1929. As The Packard Story says of 1925, “While other makers of luxury cars faded away, one by one, Packard grew richer and stronger.”

- YEAR & MAKE - 1929 Packard

- MODEL NAME - DeLuxe Eight

- SERIES - 645

- MODEL/BODY/STYLE NUMBER - Body Style 1539

- BODY TYPE - 4 Door, 5 Passenger Dual Cowl Phaeton

- BODY BY - Dietrich

- # CYLS. - Strt. 8

- TRANSMISSION TYPE & NUMBER - 3 Speed, Two Plate Clutch, RWD Hydramatic, RWD

- WEIGHT - 5,165 lbs

- ESTIMATED PRODUCTION - 2,061

- HP - 105

- C.I.D. - 384.4

- WHEELBASE - 145.5″

- PRICE NEW - $4585 - $5985

Before the Depression, as America’s economy and Packard’s fortunes spiraled upwards, Packard decided they needed a car specially for the coachbuilder’s art. Raymond Dietrich is most remembered for Lincoln bodies, but Packard retained him to help design the Model 645, which by a half-inch (over the Stearns-Knight J) had the longest wheelbase of any production car.

Where Packard fans have a favorite coachbuilder from the start of the Classic years, it’s usually Dietrich. Their bodies are both finely appointed and superbly built: “Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, Dietrich penned designs that in many ways epitomize Packard’s greatest era,” wrote Dennis Adler in Packard. “From his visions of what an automobile should look like, [Ray] Dietrich proposed features that would neither copy nor embellish on existing trends but rather establish new standards other auto makers would follow.” Certainly, the Dietrich influence in this dual cowl Sport Phaeton body can be seen expressed in cars such as the LeBaron-bodied Chrysler Imperials of a year or two later.

Packard in the Roaring Twenties behaved like an economic powerhouse in other ways, too. They certainly had the means to make major engineering changes, but showed conservatism and aside from dropping six-cylinder cars, there were no major differences in the engine lineup in the years before the Depression. You could say that none were needed. By 1929, the big 384.8-cu.in. eight made a reported 105hp in a 645, The horsepower figure was probably generous, but modern dyno runs show the long-stroke engine produces an actual 350-lbs.ft. of torque, which will motivate any car. Instead of major engineering changes, then, they offered five models with three different wheelbases and engines, and around 50 different bodies throughout the range.

All Packards were eight cylinder cars in 1929’s Sixth Series, which included the volume selling, profitable Model 626 and 633 Standard Eight on 126.5- and 133.5-inch wheelbases; the near-mythical Model 633 Speedster Eight (a true muscle car, with a special high-performance engine in the body of a small car; of 70 produced, one is known to survive); the exclusive 140.5-inch wheelbase 640 Custom Eight; and the top of the line, 145.5-inch 645 DeLuxe Eight.

With starting prices of around $5,000, Packard’s Deluxe Eights were among the most expensive and finest motorcars of their day. Competition came from makes such as Lincoln, Cadillac, Stearns-Knight and Stutz. Thirteen Individual Custom Line bodies were available on the 145.5-inch chassis, from LeBaron, Dietrich and Rollston, including this Sport Phaeton by Dietrich, which marries the Dietrich-specified chassis with Dietrich’s most spectacular body.

The styling of a 645 didn’t stop with the exterior. They fully expected the owner to want to open the hood to discuss the finer points of the iron-steel alloy block, so you will see no rough castings underhood. Any exposed hoses or wires are routed carefully and neatly, while control rods and piping were buffed nickel; aluminum was scraped flat and sandblasted and everything else was enameled in Crane Grey and black.

The Series 6 Model 645 began a lineage that included the succeeding 745 and 845. These three brief years of 145-inch and longer chassis represent a high water mark for straight-eight, long wheelbase Packards, before their Twin Six Vee engines appeared.

In 1956, after Packard’s disastrous acquisition of Studebaker, Curtiss-Wright took control of the troubled Studebaker-Packard Corporation and began to liquidate it. Unfortunately, the new financial management destroyed the bulk of Packard factory records, including build sheets and other production data for almost the entire history of Packard. The result has been a half-century of frustration for Packard owners and historians.

Despite being a very recognizable and popular body style on a distinctive chassis, this chassis 169415’s origins are obscure. However, as Packard 645 record keeper Pat Phinney points out, thanks to Curtiss-Wright that’s hardly unique: Beyond identifying the state from which it came, “I’ve got a 645 and we can’t trace it back to anything,” he says.

In this case, it’s the death of two owners within about 10 years that’s made this car an enigma. Records of its life don’t emerge until the late 1980s, when collector Bill Mackey of Flat Rock, North Carolina, bought it partially-restored from an owner who had died before he completed his car. Bill finished it in time for the 1993 Packard national meet at Asheville, where under the club’s debut of 100-point judging he scored 95 points and won his class.

However, Bill soon died as well, in the mid-1990s. Members of the Blue Ridge Packards report his wife Betty sold their house and cars, although they believe his son owned this car until Chicago Vintage Motor Carriage acquired it at Christie’s Tarrytown, New York, auction in 2000. Our research into this important Packard’s earlier history is ongoing.